:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(jpeg)/What-Is-Nouvelle-Cuisine-FT-DGTL1125-Hero-9b813a9d1ad24e859400e99c380010c1.jpg)

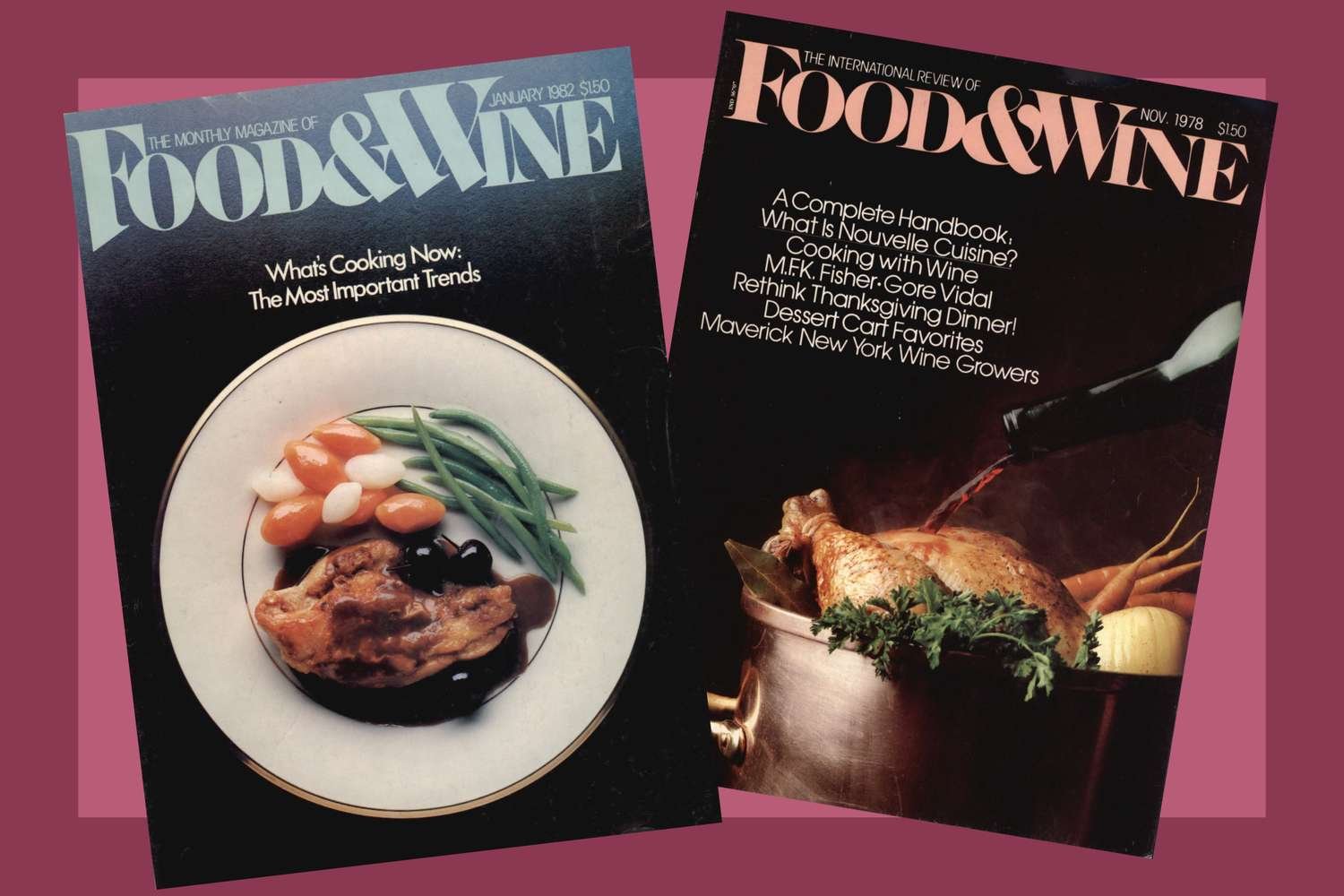

From the F&W Archives: In November 1978, just a few months into its existence, Food & Wine published a 12-page spread on the burgeoning trend of “la nouvelle cuisine” which had yet to make its way to the United States, save for the occasional ooh-la-la traveling chef dinners showcased at New York City’s temples of gastronomy. This was writer Justine de Lacy’s account of where the trend came from — and how it nearly became a parody of itself.

What is nouvelle cuisine?

Don’t take it to heart if you don’t know what a kiwi is: 99% of the French think it’s a bird from New Zealand — it is — and 99% of Americans think it’s a brand of shoe polish. But the kiwi in question — enfant terrible of nouvelle cuisine — is a fruit that hails from northern China: it’s Kelly green inside, brown and furry outside. Now kiwis aren’t all that bad. In fact, they might be downright tasty if they hadn’t come to symbolize the self-consciously exotic nature of much of what is being dished up today in the name of nouvelle cuisine.

Don’t get me wrong. There’s still much to be said for the culinary closet-cleaning now underway in France. But the trick these days is not where to find nouvelle cuisine, but how to tell the genuine article from the myriad malodorous mélanges being served in restaurants from Bordeaux to Bligny-sur-Ouche.

Meet “la bande à Bocuse”

When a group of Lyonnais chefs, commonly referred to as “la bande à Bocuse,” announced that they were launching a new style of French cooking a few years back, even cautious connoisseurs agreed that French cuisine could use a bit of shaking up. For decades it had staggered along, buried in béchamel, drowned in demi-glace, sagging under the weight of Escoffier’s elaborate directives. French chefs were judged on their ability to reproduce the classic repertoire, not on imagination.

The “nouvelle cuisine,” as the chefs called it, was to be the first real change in French cooking since Escoffier. Its tenets included lighter, flour-free sauces, shorter cooking times (or none at all, in the case of the suddenly popular raw fish), and combinations such as sweet and sour and fruit with meat, inspired by the Orient and heretofore heresy in the presentation — small bits of fish, meat, vegetables, and fruit set in quasi-geometric arrangements on large plates — also revealed an Eastern influence.

It sounded easy. With vegetable purées suddenly in fashion, for example, all you had to do was plug in a processor to be king. “Less was More,” the press proclaimed, and with that, the Emperor’s New Clothes syndrome came to France. There was just one hitch. Like abstract art, this nouvelle cuisine required a chef to be the master of basic technique before he could go his own way. (All would-be Picassos must first prove they can draw.) Or, as Raymond Oliver put it, “You must know how to make a béchamel even if you never use it.”

The nouvelle larder, according to F&W in 1978

1. Ubiquitous lattice-rimmed German-made plate

2. Raw salmon, fresh noodles, red caviar

3. Kiwis

4. Julienne of vegetables and truffles

5. Snow peas

6. Raspberries

7. Fresh coriander

8. Orange zest

9. Fresh ginger root

10. Pistachios

11. Green peppercorns

12. Sorrel

13. Undercooked duck breast

14. Creme fraiche

15. Baby-smooth vegetable purees

Undercooked duck, garlic as a vegetable, and the same salad on repeat

The problem was that only 20 or so chefs in France had acquired the combination of skill, imagination, and common sense that the grande aventure de la nouvelle cuisine required. And so, just as they had diligently duplicated the dishes of Escoffier, half the chefs in France now set about copying the nouvelle cuisine as fast as Ohrbach’s copies Cardin.

Culinary espionage took on James Bondian proportions. In a town 300 miles from Lyon and just as far from the sea, you’d find Bocuse’s sea bass en croûte. Two hundred miles from Paris they were serving Jacques Maniere’s salade folle. On a trip from Bordeaux to Burgundy last year, I was served this same salade folle five nights in a row. (This mixture of al dente green beans, foie gras, truffles, and an occasional crayfish tail also parades under the name salade gourmande, salade joyeuse, salade exquisite, etc.) Where were the great regional dishes of France?

The list of culinary clichés soon included poached fish with julienned vegetables, salmon with sorrel à la Troisgros, cold fish terrines, vegetable purée, and whole garlic cloves (ail doux) served as a vegetable. Chicken wings were big. So was duck, on condition that it be served practically raw, as magret — a duck steak whose main claim to fame is that no one can tell it’s duck — or as aiguillettes, curly slivers from under the wing.

Justine de Lacy

‘Raw duck! Raw duck!’ complained surfeited visitors to Paris, begging for addresses of restaurants where they could get a rack of lamb.

— Justine de Lacy

“Raw duck! Raw duck!” complained surfeited visitors to Paris, begging for addresses of restaurants where they could get a rack of lamb. Then, in their 1977 Guide de la France, food critics Henri Gault and Christian Millau began handing out bright red chefs’ hats — toquettes — to nouvelle cuisine restaurants, while those serving classic French dishes got run-of-the-mill black toques.

Some Gault-Millau readers were for the new system; some were not. There hadn’t been much brouhaha over the red and the black in Paris since Stendhal. Restaurants that had served traditional food of the southwest, Normandy, or Lyon now switched to nouvelle cuisine in a last-ditch attempt to trade in tired black toques for shiny new red ones. Suddenly there was a kiwi in every cocotte. Duck with kiwis. Lamb with kiwis. Candied kiwis. Kiwi sherbet. Chefs rushed to be the first on their block to sauté radishes or poach cucumbers. Parisians compared the stampede to the ’30s, when cocktails were la mode. “Then you could put anything in a glass and people would drink it,” says chef Jacques Maniere. “It was the same with the nouvelle cuisine.”

Gotta have a gimmick

There were endless debates over who had been the first to launch the magret and who had copied whom. It began to be helpful to know the right peasants: half the chefs in Paris were on a waiting list for a Basque shepherd who could find them a Pyrénées cheese no one else served. From salade folle to cuisine folle was a short step as ingredients became increasingly exotic and recherché.

If kiwis were everywhere, it was ditto for mangoes, passion fruit, kumquats, and limes. Any fruit was fine as long as it had arrived by jet. Any oil was fine as long as it wasn’t huile d’arachide — peanut oil, now viewed as banal — that has always made the best vinaigrette. Olive oil, too, was now considered a bit base and was soon replaced by walnut oil, hazelnut oil, even truffle oil, obtained not by squeezing the costly, subterranean fungi but by marinating them. Nor would good old wine vinegar suffice. It had to be vinaigre de vin de Xérès, sherry vinegar. White pepper was banished, green peppercorns exalted. All of a sudden the peripatetic poivre vert was everywhere. At a recent dinner — it took place in New York, I grant you, but the chef was French — dessert was strawberries with green peppercorns!

Justine de Lacy

Chefs now cooked not to feed, nor even to please, but to astonish.

— Justine de Lacy

This was all part of a new “gotta-have-a-gimmick” attitude not previously associated with French cuisine. Chefs now cooked not to feed, nor even to please, but to astonish. People tasted rather than ate as the nouvelle cuisine became the latest Parisian parlor game. “Guess what we had for dinner last night?” fashionable Parisians queried. It got so you were afraid to ask.

What would they dream up next? The debate raged on. The one thing no one was debating, however, was that Less was More MONEY. Prices in the nouvelle temples of antigastronomy were astronomical, and gradually, the question changed from “Guess what we ate?” to “Guess what we paid?”

What’s in a name?

While new pretentiousness was all too evident in the ingredients — would there soon be a return to the day of Carême, when thousands of larks’ tongues were consumed at a sitting? — it also appeared in the names given the new concoctions. Many were irritating misnomers used for shock value. Pot-au-feu-de-poissons, for example, suggests a fish stew. For this dish, however, each of five varieties of fish are poached separately, as are the vegetables, and served in a light cream sauce.

As appellations got longer, menus got larger and began to smack of Howard Johnsonian hyperbole uncharacteristic of the French. Fish now came with “filaments” of saffron “on a bed of” cabbage; melon arrived “under a necklace” of jambon de Parme. Watercress was no longer cresson but “petals of cresson”; leeks had become blancs de poireaux. Then there was the plat de journée. What had happened to the good old plat du jour?

Justine de Lacy

Surely when Fernand Point said, ‘Faites simple!’ — ‘keep it simple’ — he meant vocabulary, too.

— Justine de Lacy

The worst offender, though, was the poulet de Bresse pattes bleues, a name that leads you to believe this is a special Bresse chicken with blue feet, when all true-blue Bresse chickens have blue feet. Surely when Fernand Point said, “Faites simple!” — “keep it simple” — he meant vocabulary, too.

A return to the basics

But there are no revolutions without excess — as Robespierre found out — and today it looks as if the nouvelle cuisine is at last coming into its own. Its incontestable contributions — shorter cooking times for fish, the rehabilitation of the vegetable, emphasis on color and design — are here to stay, while many of the most flagrant abuses are on the wane. Chefs in the provinces may still be slapping foie gras and green beans together in hopes of getting a red toque, but in Paris, at least, the salade folle has at last bitten the dust.

Yet this is France, and now that food can go out of style as fast as dresses, 1978 has spawned its own culinary clichés: jambon d’oie, delicious meat from the wing of the goose, smoked over beech wood and served en salade; the ubiquitous soupe de fruits, an uncooked compote, usually served with fresh mint; and seaweed that looks like tiny green beans but is crunchier. One maître d’ proudly described the exact spot in Brittany from which this wondrous tuft springs. He was crushed when I told him I’d had it the day before for lunch.

Jean-Pierre Morot-Gaudry

You can make anyone happy with truffles and foie gras.

— Jean-Pierre Morot-Gaudry

Today, however, many of the best nouvelle cuisine chefs are abandoning once-standard features like vegetable purées for more varied ways of cooking vegetables — delicious, silver-dollar-sized crêpes of corn or green beans, for example — and commonly available fruits such as currants seem to be edging out the kiwi. These days I only see ail doux on occasion, about as often as last year’s espadrille. And, in place of such once de rigueur luxury ingredients as crayfish, foie gras, and truffles — among the reasons why the nouvelle cuisine costs so much — the better chefs are finding a challenge in adapting the less expensive foods and lightening such delicious but leaden dishes as cassoulet.

“You can make anyone happy with truffles and foie gras,” says chef Jean-Pierre Morot-Gaudry, who has invented a nouvelle cuisine version of boeuf bourguignon using the once-scorned joue de boeuf, cow’s cheek. Worried that the great regional dishes of France may die out, some chefs are considering putting a few of the specialties of their hometowns back on their menus. Paradoxically, the best nouvelle cuisine chefs today are circumspect about using such a label. They prefer “cuisine nouvelle” which, in French, implies adaptation and interpretation rather than the invention and creation that are suggested when the adjective comes first. They are careful to point out that this is not a revolution but an evolution. “To be honest,” says Jacques Maniere, “I’ve only created five or six dishes in my life. And four of them, I didn’t like.”