Andean Baroque – The Sacred Fusion of Mountains and Faith

The Andean Baroque emerged in colonial Peru between 1680 and 1780, creating something extraordinary where Spanish colonial influences met indigenous craftsmanship in the highlands. This style flourished as a unique school of carving distinguished by its virtuoso combination of European late Renaissance and Baroque forms with Andean sacred and profane symbolism, some originating in the pre-Hispanic era. What makes this architectural style truly remarkable is how the mermaid appears in churches bordering Lake Titicaca, remembering the Indigenous tradition of two fish women who seduced the god Tunupa.

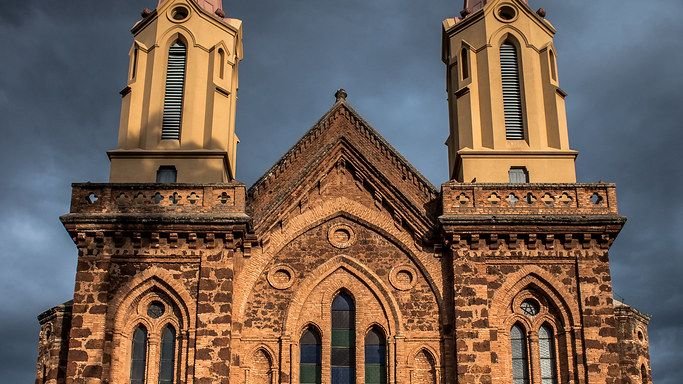

The Cathedral of Cusco in Peru and the Church of San Lorenzo in Potosí, Bolivia stand as prime examples where European technical expertise merged with Andean worldviews. These facades feature intricate carvings and ornate decoration, reflecting the blend of European and indigenous influences with motifs that include both traditions.

Mestizo Baroque – Where Two Worlds Collided in Stone

The fusion of Spanish colonial influences with indigenous elements gave rise to a unique architectural style known as “mestizo baroque” during the colonial era. This wasn’t simply European architecture transplanted to the Americas – it represented a genuine cultural synthesis. Colonial artists adapted the European Baroque to local context by incorporating elements, traditions, symbols, and beliefs of indigenous origins, with this blending contributing to the development of a distinct colonial visual aesthetic.

Baroque-influenced architecture stands out with ornate facades, rich decorative elements, and the ultimate Baroque characteristic reflected in the horror vacui – fear of empty spaces. The style became particularly notable in cities like Cuzco, Lima, and Puebla, where the opulence of the baroque blends with indigenous and mestizo elements.

Brazilian Colonial Baroque – Aleijadinho’s Revolutionary Vision

Brazil developed its own distinct interpretation of colonial baroque architecture, particularly in the gold-rich region of Minas Gerais. The discovery of gold and diamonds in these highlands created an economic force independent of the coasts and produced a unique culture. Born to architect Manoel Francisco Lisboa and an African slave in Ouro Prêto in the 1730s, Aleijadinho lived until 1814, suffering from what may have been leprosy and eventually having sculpting tools strapped to his forearms to continue working.

The work of Aleijadinho makes this remote region of Brazil an unexpectedly stimulating architectural destination. In 1774 Aleijadinho designed two masterpieces of Brazilian Baroque architecture: the Franciscan church in São João d’El Rei and the Church of St. His innovative approach to curved facades and sculptural integration created a uniquely Brazilian baroque vocabulary that influenced architecture throughout the region.

Spanish Colonial Mission Style – Fortress Churches of the Frontier

Spanish settlements and architecture can be classified as three distinct types: pueblos (civic settlements), presidios (fortified military bastions), and missions (regional churches designed to promote Catholic faith to Native Americans). In the American Southwest, Spanish colonists relied on single-story adobe structures with flat roofs and parapets, while mission churches were typically more elaborate with Baroque elements, becoming simpler and smaller the further north from Mexico.

Mission San Xavier del Bac in Tucson, with construction beginning in 1783, represents the best surviving example of Spanish Baroque architecture in the U.S., featuring local building materials, especially adobe, and simplified Baroque-style features. These missions created a distinctive architectural language that balanced European ecclesiastical traditions with practical frontier needs and indigenous building techniques.

Potosí Colonial Architecture – Silver City Splendor

The Bolivian city of Potosí is considered the cradle of the Andean Baroque with the Cathedral of the Imperial Villa featuring viceregal baroque style and neoclassical influence. Potosí served as the largest silver supplier to Spain during the colonial period, hailed as the world’s largest industrial park in the 16th century with about 160,000 inhabitants living there in the 17th century.

The Torre de la Iglesia de la Compañía, built in the 17th century by Jesuits, stands as an outstanding example of Andean baroque reaching approximately 46 meters in height and featuring ornamental details like columns, niches and friezes carved in stone. This wealth from silver mining enabled elaborate architectural projects that showcased both European craftsmanship and local indigenous artistic traditions.

Cusco Colonial Hybrid Architecture – Inca Foundations, Spanish Aspirations

The Convent of Santo Domingo in Cuzco offers an early glimpse into evangelizing zeal, built directly on remains of the Coricancha, Cuzco’s most important Inka religious temple founded by Dominicans in 1534. The finely cut masonry and trapezoidal windows of the original Inka structure became juxtaposed with the convent’s Baroque architectural flourishes, with the former temple’s function becoming intertwined with Christian notions of divinity.

This architectural palimpsest represents more than simple reuse of materials – it embodies the complex cultural negotiations of colonial Peru. The placement of a Spanish Christian structure atop a decapitated Inka temple is a symbolic act of power and subjugation, yet the visible indigenous stonework creates a powerful visual dialogue between architectural traditions.

Minas Gerais Church Architecture – Golden Age Curves and Innovation

An interesting regional style developed in Minas Gerais, a wealthy gold-mining area, with several churches built in Ouro Prêto, including Nossa Senhora do Rosário (1785) showing the typical tendency toward curving forms. Unlike Peru, Brazil is not threatened by earthquakes, allowing baroque architects freedom to experiment with more inventive forms without designing quake-proof buildings.

The Church of Our Lady of Pilar de Ouro Prêto (1730s), attributed to António Francisco Lisboa, features a rectilinear exterior with polygonal interior – a faceted oval that precedes the oval plan, marking the first of extraordinary Baroque churches designed by the Lisboa clan. This architectural innovation influenced church design throughout colonial Brazil and established Minas Gerais as a center of baroque experimentation.

Mexican Churrigueresque – Ornamental Excess as Sacred Expression

Between 1680 and 1720, the Churriguera family popularized Guarini’s blend of Solomonic columns and Composite order, with the Churrigueresque column (estipite) in inverted cone or obelisk shape established as central ornamental decoration between 1720 and 1760. The combination of Native American and Moorish decorative influences with extremely expressive interpretation of Churrigueresque idiom accounts for the full-bodied character of Baroque in Spanish American colonies, developing as a style of stucco decoration.

In New Spain, the somber European style of Mexico City’s Cathedral was abandoned in smaller urban centers where more expressive styles took hold, exemplified by the brightly colored plasterwork covering the magnificent Rosary Chapel in Puebla’s Monastery Church of Santo Domingo. This Mexican interpretation pushed baroque ornamentation to unprecedented levels of complexity and visual richness.

Collao Highland Temple Architecture – Altiplano Sacred Spaces

During viceroyalty years, large temples with single naves, Renaissance façades and Mudejar coffered ceilings prevailed in the Collao region during the second half of the 16th and first third of 17th centuries, later replaced by baroque buildings due to mining development and trade with Potosí. The temples of San Francisco de Asis de Ayaviri, San Geronimo de Asillo, Santiago Apóstol de Lampa, San Carlos de Puno, San Pedro Mártir de Juli, and others serve as architectural icons of Andean art history.

These structures emphasize side altarpiece covers under shelter arches showing profuse ornamentation with Andean flora and fauna motifs, featuring undulating profiles from vault configurations. The Collao region’s unique geographic position created architectural solutions specifically adapted to the harsh altiplano environment while maintaining sophisticated decorative programs.

Neo-Andean Contemporary Architecture – Decolonizing Modern Design

Local architect Freddy Mamani designed an emerging style known as Neo-Andean architecture, featuring colorful exterior pigments with large glass panels that clearly attracts attention in high-altitude cities of bare bricks and monochrome. Neo-Andean architecture rejects minimalist and Baroque styles preferred by Western traditional architects, marking “decolonization of symbolic order” while promoting Bolivian culture to show and maintain indigenous roots and identity.

This contemporary movement represents a radical departure from both colonial and international modernist traditions. Current trends highlight increased focus on sustainability and integration with natural and urban environments through local materials and resources, combining traditional and ancestral techniques with contemporary demands. Neo-Andean architecture challenges architectural orthodoxies while creating visually striking buildings that celebrate indigenous cultural identity in modern urban contexts.

Conclusion

These ten unique architectural styles demonstrate how Latin America developed its own architectural languages through centuries of cultural exchange, adaptation, and innovation. From the highland churches of the Andes to the gold-funded baroque experiments of Minas Gerais, each style represents specific responses to geography, climate, available materials, and cultural imperatives. The region’s architecture tells stories of conquest and resistance, wealth and poverty, indigenous wisdom and European technique – all crystallized in stone, adobe, and ornament.

What’s most remarkable is how these styles continue evolving today, with Neo-Andean architecture proving that Latin American architectural innovation remains vibrant and culturally relevant. Who would have thought that a continent once seen as architecturally peripheral would produce such distinctive and influential building traditions?